What did Islam mean to medieval Muslims?

“Allah will raise for this community at the end of every 100 years the one who will renovate its religion for it” – Sunan Abu Dawood, Book 37: Kitab al-Malahim [Battles], Hadith Number 4728

Islam’s universally accepted definition is one “who submits to God”, and one who testifies and believes that there is one God and Muhammad is His Messenger is regarded a Muslim. However, the laws of Islamic theology and cultural practices of Muslims do not always fall in line, as pointed out by Shahab Ahmed, who distinguishes Islam as a “historical and human phenomenon” in order to convey Islam as a human fact in history rather than a matter of Divine Command. This is understandable considering the sectarianism, political fragmentation, and diversity of Islamic civilisations. However, this essay will argue that orthodox Islamic principles that originated from the Qur’an and hadiths were the understandings that prevailed amongst the majority of medieval Muslims in the midst of divergent cultural and societal practices. This essay will begin by establishing the prominence of the Qur’an, hadith, and Sunnah in medieval Muslims lives, and then address the sectarian and cultural differences within Islam, and end with the legacy left behind by Muslims in this period.

In order to understand what Islam meant for medieval Muslims, we must acknowledge the Qur’an and hadith held immeasurable weight in Islamic societies and were the main sources of acquiring information for medieval Muslims, whether it be a Muslim in in Al-Andalus or Southeast Asia. The verses of the Qur’an addressed every corner of political, economic, and social wellbeing, on top of the lessons of the prophets and Afterlife, which would shape a Muslim’s conduct and lifestyle. This included foreign relations, trading, contracts, oaths, marriage, death, warfare and so forth. The Qur’an is unequivocally clear about five things: the Oneness of God, prayer, fasting, charity, and belief in the Last Day and Afterlife – Paradise and Hellfire (2:177). To falter on these commands would mean sinning, but to change or reject one would mean leaving the bounds of Islam and thus can be considered un-Islamic, as a fundamental characteristic of Islam is its finality and perfection, shown by the verse, “This is the day, I have perfected your religion for you…” (5:3). Ibn-Kathir in his exegesis said that on the day this verse was revealed – ‘Day of Arafat’, 630 CE – the religion was complete and any new additions to it would be deemed innovation and therefore outside the fold of Islam. This can be seen when analysing the linguistics of the Qur’an, where it states those that falter on commands are “transgressors” or “sinners”, and thus can be forgiven through repentance. But when talking about those who alter the word of Allah or reject them, they are labelled either “astray”, “disbeliever” or “hypocrite”, followed by “they will abide therein [Hellfire] eternally” or “for them, there is no reprieve.”

Hadith literature is routinely rejected as a historical source, due to its reliability and geographic and time discrepancies, but for medieval Muslims hadiths played crucial role and was second to the Qur’an. Although the Western narrative portrays hadith transmission as a simple game of Chinese whispers leading back to the Prophet, hadiths were preserved with far more diligence. Memorisation and oral transmissions were fundamental in the Mediterranean due to the low literacy rates, and even after Islam arrived and literacy increased, oral transmissions continued as the practice was so ingrained in society. Furthermore, the positions of those within the chain of narrations held great value and were not ordinary people, but either sahaba (direct companions), tabi’een (descendants of companions), or scholars. As the tabi’een lessened in the 8th century, hadiths became transmitted from scholars to students who became scholars and passed it onto their students, as seen by the sahaba Ja’far al-Sadiq who taught hadith to student and tab’iee Malik ibn Anas, who became a scholar and taught ash-Shafi’I, who created one of the biggest madhab’s (school of thought). Both scholars and students took immense pride in protecting hadiths knowing the authority of the religions laws depended on it, and Imam Malik constantly reminded his students of the verse, “Indeed, those who exchange the covenant of Allah and their [own] oaths for a small price will have no share in the Hereafter, and Allah will not speak to them or look at them on the Day of Resurrection.” Students of hadith Sa’eed ibn Musayyib said, “I used to travel for days and nights at a time to search out for a single hadith”, and Rafi ibn Mehran said, “We were not satisfied until we travelled to Al-Madinah to hear it directly from their [scholars] mouths.” Despite scholar’s best efforts, hadiths still became forged over the centuries. However, al-Bukhari’s lifetimes work in the 9th century of authenticating hadiths using a rigorous process of ranking hadiths (sahih – genuine, hasan – strong, daif – weak, mawdu – fabricated) and removing all hadiths with a single person with a negative record in the chain, and was left with 8 volumes of authentic hadiths with strong chains of narrations – the collection is regarded as the second most authentic source behind the Qur’an.

This would set the foundations of modern-day Islamic hadith science and the following decades would see more hadith collections following this same authentication process, such as Tirmidhi, Abu Dawood and Ibn Majah. Thousands of sahih hadiths with strong chains of narration would formulate Islamic law in several Muslim societies, and more importantly, the Sunnah – the prophetic lifestyle that were to be emulated as best as they could by its believers. Al-Ghazali outlined the importance of observing the Sunnah, stating, “Know that the key to happiness is to follow the Sunnah [Muhammad’s actions] and to imitate the Messenger of God in all his coming and going, his movement and rest, in his way of eating, his attitude, his sleep and his talk.” The practice of the Sunnah was so extensive and widespread it gained the name imitatio Muhammadi in the Western worlds. It gave uniformity of action, a clear objective, and a guideline for children’s upbringing for Muslims from Morocco all the way to Thailand.

One of the primary reasons as to why Shahab Ahmed and other historians found difficulty in answering what Islam meant was due to the sectarianism within the religion. However, due to the breadth of size and regions Islam enveloped, alternate interpretations of the Qur’an and hadith were inevitable. Therefore, these sects, schisms and movements all have strong explanations pinpointing their deviance from the orthodoxy of Islam. A sahih hadith with a strong chain narrated in Abu Dawood says that Muhammad said, “The Jews have divided themselves into 71 different sects. As for the Christian, they divided themselves into 72 sects. As for this ummah, it would divide into 73 sects. All of these sects will be inside the Hellfire, except for one.” The companions then asked, “who will be the sect saved from Hellfire?” Muhammad responded, “They are those who are upon that which I am upon and my companions are upon.” From the hadith can be extracted three things, a) Muhammad knew Islam would divide into many sects believing it to be normative of a nation that grew as big as Islam did, b) sectarian and unorthodox beliefs would exile even professed “Muslims” to Hellfire, and c) the importance of sticking to the Sunnah, so as not to be deviated from Islamic orthodoxy.

Fragmentation of Islamic orthodoxy began with the Khajirites in 658, meaning “The Ones Who Left”, and in the next centuries this group would splinter into other groups that would themselves fragment, hence within Shi’ism there are the Ismai’ilis, Twelver’s, Jafris and so on. Shi’ite history is entrenched with upending the established order, beginning with the rejection of Abu Bakr’s caliphate and the Islamic civil wars in the 7th century. Eventually, what began a revolutionary political movement became religiously instituted through several theological alterations to the orthodox Islamic doctrine. Ehsan Zaheer notes that the elevation of Ali and projection of the Imamate had no foundations in the Qur’an and hadith, and therefore, Shi’a “orthodoxy” is established upon false promises and misguidance. To rectify this, Zaheer added, Shi’ite scholars created separate hadith books to supplement these mistruths, and replaced thousands of hadiths with that of Ali and the Imams. One can see the false promises even in the institutionalised Shi’a empires such as the convenient arrival of the 12th imam in Ibn Hasan al-Aksari in 868 and Isma’il’s apparent lineage to Ali in the 16th century for Twelver Shi’ites – of which there is no clear historical evidence – or a Berber tribesmen declaring himself descendent of Fatima and Ali upon which the Fatimid’s, Ismai’ili, and Sevener Shi’ites were founded upon. But just as problematic is the Shi’ites predication on weak historical grounds is the alteration of the orthodox principles of monotheism, such as elevating Ali’s position and directing prayers towards him, which Ibn Taymiyyah in his refutation of the Shi’a stated those that accepted this practice were committing shirk, the greatest sin.

Sufism is different however, as it transcends sectarianism as it is more of an amorphous movement that is practiced within both Sunni and Shi’ite traditions. It is regarded as “the spiritual dimension” of Islam, characterised by asceticism and mysticism, and some regard Sufism as within the tenets of Sunni Islam as it shares many key focuses, such as purification of the soul, closeness to God, and denunciating worldly affairs. But more importantly, the fundamental doctrines of Islam, such as monotheism and adherence to the Qur’an and Sunnah are observed within Sufism, unlike the Shi’I “doctrines” – which are sparsely different within themselves. Therefore, despite Halil Inalcik’s assertion that early Ottomans “studiously patronised Hanafi Sunni Islam” and Dale Stephen’s point that the Hanafi School prevailed in Muslim India in the midst of various Sufi orders, the Sufism within Anatolia and the Indian subcontinent would not negate the fact that orthodox Islamic principles prevailed within these regions.

After the growth of empirical sciences and philosophy in the Islamic worlds, new Muslim theorists emerged believing rationality and reason presided over revelation. Among them are the Mu’atazil, Ash’ari and Maturidyya, all of whom differed among themselves as to the degree rationality plays within Islam. But in his refutation of these groups, Ibn Taymiyyah described most of these philosophical debates as “Greek solutions for Greek problems” that should never have concerned Islam in the first place, noting that Islam had been perfected and finalised with the last verse of the Qur’an. There are two key points to note when discussing these sects. Firstly, these theological nuances were mainly constrained to scholarly debates and rarely found themselves in mainstream Muslim society, hence why they never gained popularity. Secondly, Al-Ghazali’s refutation of philosophers in the 12th century would bring an end to radical philosophical approaches to Islam, clearly stating that Islam did not refute science nor did science refute Islam, but those that breach Islamic orthodoxy through denial of God’s attributes, Resurrection or other fundamental Islamic principles, have entered the realms of heresy.

Another reason why Shahab Ahmad distinguished the historical fact of Islam from its theology was due to the contradictions in the cultural practices of Muslims and Islamic law. There are countless examples, for instance, the Umayyad’s were described as “impious kings”, the “song-wine-and-dance” of the Persianized Abbasid courts, and Ibn Battuta was often surprised by local customs as they did not fit with his orthodox Islamic education. This is best characterised by the poetry of Abu Nawas which revolved around all forms of debauchery and the joys of being “drunk and drunk again”, and who some Abbasid caliphs admired while others imprisoned. Despite the acts of impiety, it is important to understand that it did not extend to the entire Muslim population as many voiced – or kept to themselves – their disapproval with the indulgences of the caliphs and high courts, and many wanted a return to the prophetic teachings – one of the key reasons as to why the Abbasids came to power promising this exact demand. Islam certainly meant different things to different Muslim ruling elites, such as Abbasid Al-Ma’mun enforcing the Mu’atazil doctrine on his subjects, Mughal Akbar’s Din-al-Ilahi religion, and Tamerlane claiming to conquer in the name of Islam, but replicating the vicious, barbaric, and un-Islamic warfare of Genghis Khan.

Therefore, rather than focusing on the behaviours of the imperial elites and rulers to dictate what medieval Muslims were like, it is more effective to see what they supported as this is more reflective of the majority of the medieval Muslim views. As mentioned before, a key reason as to why the Abbasids came to power in 750 was the promise of a return to prophetic traditions. This would be a continuous theme for medieval Muslims, seen in the instance of the Mihna, whereby the medieval Muslim population resisted Al-Ma’mun’s Mu’atazil doctrine and sided with the scholars and as such the caliphate would be reduced to a symbolic role and the ulama took precedence. Another instance was the Almoravid and Almohad movements, or Murabitun in Arabic meaning, “Those Who Hold Fast”. Its straightforward message of returning to prophetic traditions, promoting righteousness, and removing injustice and un-Islamic taxes gained widespread popularity in North Africa and West Africa, and then extending all the way to Al-Andalus, where they played huge roles in sustaining an Islamic foothold in the Iberian Peninsula for a century. Salah al-Din Ayyubi was able to unite Egypt and Syria unopposed and with far-reaching public support for the first time since the Fatimid’s uprising, as the people greatly embraced his orthodox religious reforms as opposed to the Shi’I Fatimid’s, and thus began the Ayyubid Dynasty. Mughal Aurangzeb’s Fatawe-e-Alamgiri which established Islamic shari’iah was greatly welcomed by its Hanafi and Sunni dominated Muslims in 17th century India, as was Sultan Suleiman’s religious and legal reforms in the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century. A recurrent pattern emerges throughout medieval Islamic history, that when a return to the Sunnah and orthodox Islamic traditions are made, it mobilised and rejuvenated its Muslim populations, however short-lived.

One of the best ways to answer what Islam meant for medieval Muslims is to see the most profound and lasting legacies that they left behind. Medieval Islam comprised immense scientific, mathematic, and philosophical advancement which was promoted by Quranic verses, such as “Travel the land, and observe how He began creation” (29:20) and hadiths such as, “Whoever takes a path in search of knowledge, Allah will cause him to walk in one of the paths to Paradise.” Such rewards would suggest that Islamic principles of seeking knowledge were key motivators for al-Khwarizmi, Ibn Haythem, Ibn Battuta, and al-Razi on astrology, astronomy, mathematics, geography, and medicine, particularly the case of al-Battani, whose works on astronomy were to help Muslims calculate the direction to pray towards Mecca. Many began their works stating “In the name of Allah…”, or citing their pages with the aforementioned Quranic verses and hadith outlining the benefits of seeking knowledge, as seen by the manuscript of Ibn Sa’id. Ibn al-Razi believed medical practice was a sacred endeavour as doctors are entrusted by God to protect human lives, and Ibn Haythem said, “I constantly sought knowledge and truth, and it became my belief that for gaining closeness to God, there is no better way than that of searching for truth.”

However, the majority of medieval Muslims that were not scholars or intellectuals, but sedentary commoners and nomads. There are two factors to note when discussing this section of Muslims. Firstly, just as the western worlds were beginning to become Christianised, as were the Muslim worlds but with much greater focus on knowledge, with bureaucratic figures and scholars proclaiming education should be proscribed upon everyone, such as al-Din al-Marghinani. As such, Muslims enjoyed high literacy rates, particularly in Baghdad, Damascus, Madinah, Cairo, and Cordoba, with the otium of all these Islamic societies relating to seeking knowledge or religious practice. Secondly, as Berbers, Turks, Persians, Andalusians and so forth converted to Islam, the notion of Islam as an ‘Arab religion’ was dispelled. Al-Istikhari’s 10th century map shows the cosmopolitan Islamic regions, that would otherwise have had little in common were it not interconnected through Islam, which enabled flowing trade. Ibn Khaldun’s Muqaddimah is regarded as the first works of sociological research, and in it he mentioned the zealous religious enthusiasm of the nomadic peoples, noting in particular the North African Berbers and their observance of “prayer, almsgiving, gifts, and chastity”, accrediting it to their tribal units as opposed to the luxuries and wealth of the cities. Ibn Battuta mentioned the religious enthusiasm and well-kept mosques in the cities of Kilwa and Mombasa in East Africa, and the Sultans of Mogadishu and Kilwa who strongly supported the ulama, and notes the religious effect left in Timbuktu of West Africa, with the legacies of Mansa Musa still prevalent in Mamluk records. He was also surprised by the religiosity within China and Southeast Asia, particularly Pasay, despite being far from the central Islamic lands, but were unified the Qur’an, prayer, Ramadan, following the Sunnah, and Arabic as a lingua-franca.

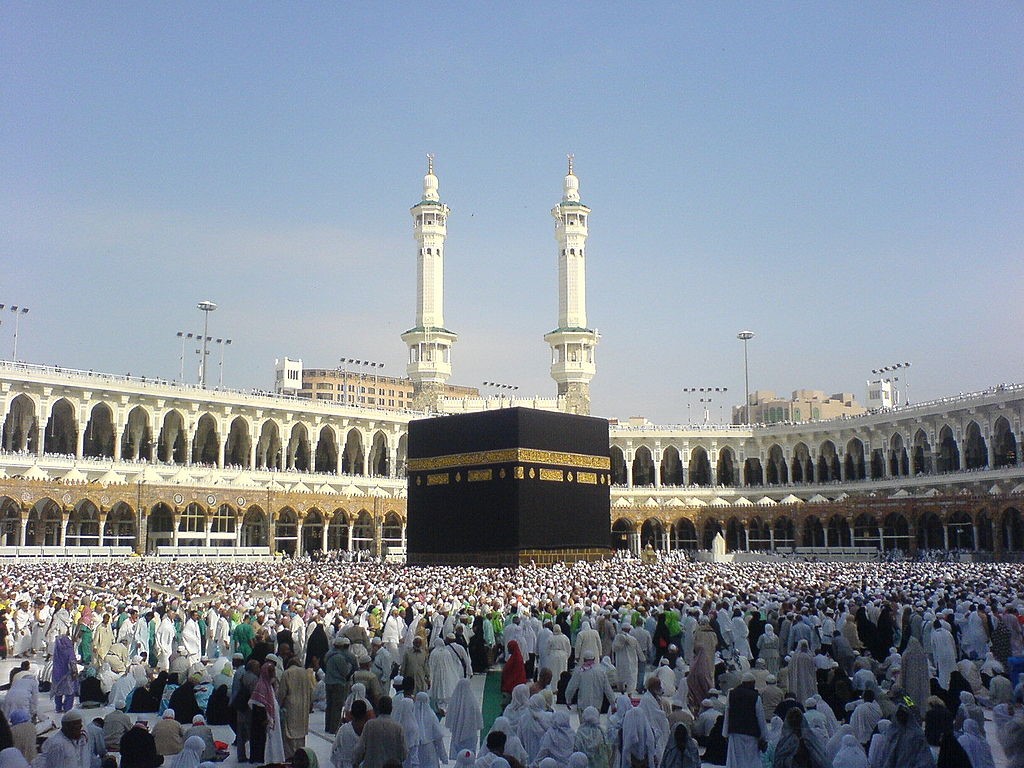

Indeed, there is evidence of Islam’s interpretation varying among medieval Muslims and as pointed out by Shahab Ahmed, various cultural practices within Islamic civilisations, but the fundamental principles of Islam have remained the same throughout the medieval period. This is not only seen by the historical legacies of medieval Muslims, but the most definitive proof is that the adherence to the Qur’an, hadith and Sunnah did not diminish in the 14 centuries of Islam, with 85-90% of the 1.8 billion modern Islamic population being Sunni Muslims, 3.85 million mosques facing the Kaaba, and only one recognised Qur’an. The deviation within Islam can be pinpointed and accounted for, but is best summarised by the verse in which Ibn Taymiyyah ends his Kitab al-Iman, “Had Allah willed, He would have made you one nation, but [He intended] to test you in what He has given you; so race to good. To Allah is your return all together, and He will inform you concerning that over which you used to differ (5:48).”[35]