Is the ‘elite manipulation’ argument sufficient for explaining the success of the Pakistan movement in the 1940s?

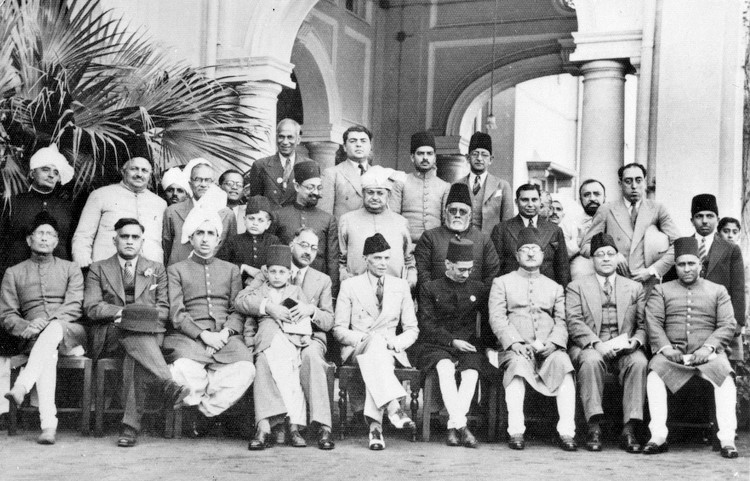

A subset of Founding Fathers of Pakistan met in Lahore in 1940 to discuss the idea of Pakistan

A subset of Founding Fathers of Pakistan met in Lahore in 1940 to discuss the idea of Pakistan

The Pakistan Movement was a political campaign that aimed and succeeded in the creation of the Dominion of Pakistan from the Muslim-majority provinces of British India in 1947. However, scholars explaining the partition have found difficulty in placing the success of the movement due to the complications in reconciling the ‘popular’ narrative, where common people supported its creation, and the ‘elite’ narrative, where the ‘high politics’ of the political elite is believed to have manipulated and controlled this support to safeguard their own interests. This essay will attempt to demonstrate that ‘elite manipulation’ played a key role in the creation of Pakistan, and this will be achieved by firstly discussing the various historiographical interpretations of Pakistan’s formation in order to ground the argument among the various narratives in this field. Secondly, by analysing the character of the speeches in the 1930s and the Lahore Resolution in 1940, this will demonstrate the vague and ‘non-territorial’ vision of Pakistan that led to its widespread support. Lastly, by discussing the methods of political campaigning the Muslim League (ML) utilised, focusing particularly on Punjab, Sindh, and the North-West Frontier, this will demonstrate the ML’s instrumentalization of religion, its role in communal violence, and its propaganda techniques.

Ayesha Jalal’s works have become the orthodoxy in explaining the causes of Pakistan’s creation, where she explores the movement through the Quad-i-Azam, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, and his role as the ‘Sole Spokesman’ of the Muslim League. She argues that the creation of Pakistan was not from Jinnah’s single-minded commitment to a separate nation state or as a result of a ‘grand ideological project’, but instead as the ‘fallout of a strategic game of chess played by Jinnah’, as the Cabinet Mission Plan that envisioned Muslims and Hindus sharing political power in a federal setup was Jinnah’s real aim, not a separate sovereign Pakistan. Consequently she describes Pakistan as a ‘bargaining counter’ for obtaining political equality for Muslims in an undivided India. She further contends that Jinnah’s unwavering commitment to Pakistan was derived primarily from his desire to gain recognition as the ‘sole spokesmen’ for all of India’s Muslims, and the obsession was rooted in the in reality that he was not in fact the exclusive political voice of Muslims.

Jalal’s works have faced considerable criticism, with Gyanendra Pandey inculpating her of providing a lack of recognition to local level politics and the “grassroots” concern of most Muslims due to Jalal’s emphasis on high politics. However, Jalal’s focus on Jinnah is not to suggest that the only the history of elite Muslim leadership matters in the partition narrative, but the agency and actions of Muslims – which were varied and diverse in the demand for Pakistan – was central to the partition story. Anita Singh in her response to Jalal, while arguing that Jinnah had a clear vision of Pakistan as a separate sovereign state and outwitted Britain and the Indian National Congress (INC) to achieve its creation, still concedes that Pakistan was an unclear concept that meant ‘all things to all Muslims’. David Gilmartin goes further by suggesting that without Muslim divisions, there might not have been a partition or Pakistan at all.

In attempting to plug the gaps of her works, Gilmartin reconciles the relationship of high politics and popular violence. Critical to explaining the inception of Pakistan, he believes, is understanding how Muslims themselves understood Pakistan. Through examining the discourse of territorial nationalism, he concluded that the diverse identities and contexts in which the support of the Pakistan Movement acquired was as a result of its ‘non-territorial conception’, as Pakistan was seen by most as a ‘transcendental symbol of Muslim community’ rather than a territorial nation-state located in a specific area of India. Therefore, the idea of Pakistan as a Muslim state was not so much to create a ‘territorial homeland’ for Indian Muslims, as it was to establish a moral and political symbolic centre to the concept of a united ‘Muslim community’ in India, and Jalal would further contend that it was this ‘Muslim community’ that would provide Jinnah the symbolic capital he required to identify himself as the image of Muslim unity.

The first notion of a separate nation state was floated in the 1930s. Until the mid-1930s, the Muslim League had remained an organisation of elite Indian Muslims that were toiling to obtain political security for Muslim majority provinces within the framework of the Indian Federation. The INC formed government in six out of eight of these provinces, and thus much of the early ML propaganda was directed against the Congress and their alleged inability to protect Muslim interests and their ‘attacks’ on Islamic culture. In the All-India Muslim League annual session on 29 December 1930, Sir Muhammad Iqbal stated in his presidential address:

I would like to see the Punjab, North-West Frontier Province, Sind, and Baluchistan amalgamated into a single State. Self-government within the British Empire or without the British Empire, the formation of a consolidated North-West Indian Muslim State appears to me to be the final destiny of the Muslims, at least of North-West India.

The term “Pakistan” was not mentioned in the address, leading many scholars to suggest that Iqbal never pleaded for the partition of India, but was a proponent of a ‘true federal setup’ that consolidated the Muslim majority within the Indian Federation. Consequently, various territorial configurations and plans of Pakistan were put forth by subsequent leaders, and critics were quick to point out the confusion it caused, with Jawaharlal Nehru noting, “Iqbal was one of the early advocates of Pakistan and yet he appears to have realised its inherent danger and absurdity… he felt sure that it would be injurious to India as a whole and to Muslims especially.” Nonetheless, through the combination of increased communal tensions, anti-Congress propaganda, and Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s processions and rallies, the ML leadership began to mobilise large groups of support, with its earliest bases in the United Provinces. In 1940 at the League Conference, Jinnah stated:

Hindus and Muslims belong to two different religious philosophies, social customs, literature... It is quite clear that Hindus and Mussalman’s derive their inspiration from different sources of history. They have different epics, different heroes, and different episodes... To yoke together two such nations under a single state, one as a numerical minority and the other as a majority must lead to growing discontent and final destruction of any fabric that may be so built up for the government of such a state.

Jinnah places a clear demarcation between Hindus and Muslims, not just along religious divisions, but as two separate communities with different histories and customs, therefore needing two separate nations. Faisal Devji claims that instead of attempting to invoke the past, Jinnah was interested in reducing the categories of Hindus and Muslims to “legal and juridical lines to allow for a successful negotiation of a social contract between the two.” In legal and juridical terms, the pronouncement of the demand of a separate sovereign state was made by the Lahore Resolution, however David Gilmartin notes that Jinnah had always remained ‘extraordinarily vague’ in his calls for Pakistan as a clearly demarcated territorial state, and Ayesha Jalal further contends that “from first to last, Jinnah avoided giving the demand a precise definition, leaving the League’s followers to make of it what they wished.” The second article of the Lahore Resolution was the first clear-cut mentioning of demarcated territories by the ML:

… no constitutional plan would be workable in this country or acceptable to Muslims unless it is designed on the following basic principle, namely that geographically contiguous units are demarcated into regions which should be so constituted, with such territorial readjustments as may be necessary, that the areas in which the Muslims are numerically in a majority as in the North-Western and Eastern Zones of India, should be grouped and constitute “Independent States” in which the constituent units shall be autonomous and sovereign.

Though the Lahore Resolution identified the ‘North-Western and Eastern Zones’ as the marked out territories and Jinnah had vaguely suggested Pakistan would be a region where Muslims were a majority in, Gilmartin argues the ‘two-nation theory’ had always embodied a fundamentally “non-territorial vision of nationality.” The realm of territory was marked by a language of communalist self-assertion with a concern for unity and a search for moral order. However, these images of unity and morality that were constructed were often dissimilar with the structure of a territorially marked sovereign state, which was instead a site of debate and competition. Faisal Devji notes that the “old moral city” of mosques, courts, markets, and schools had been displaced by the realm of print and public meetings as the stage for the representation of the Muslim’s ‘moral collectively’.

The opposition to the Lahore Resolution not only resembled the inchoate aspirations of Muslims towards the creation of Pakistan, but also beginning of the exploitative machinations the political elites utilised to gain advantages over those that opposed them. During the ‘All India Azad Muslim Conference’ in April 1940, several groups gathered to voice the opposition to the Lahore Resolution and support for a united-India. The groups included 1,400 nationalist Muslim delegates and several Indian Islamic organisations, and the meeting was said to outweigh the Muslim League meeting attendance figures by ‘five times’. In their attempts to quell the opposition, the ML often utilised coercion or intimidation, the most prime example being with Deobandi scholar Maulana Syed Husain Ahmad Madani. The scholar travelled across India promoting his book Composite Nationalism and Islam which espoused Hindu-Muslim unity, but while he did this, ML activists would attack, intimidate and terrorise Madani, his rallies, and his supporters.

The 1946 provincial elections resulted in the Muslim League winning the majority of Muslim seats in the central and provincial assemblies (425 out of 476 seats reserved for Muslims and 89.2% of Muslim votes) and was effectively the plebiscite in which Indian Muslims voted for the creation of Pakistan. But how can this support be accounted for? Through the examination of several key provinces in the build-up to the elections, the manipulation, scheming, and abuses of power become more evident. Beginning in Punjab, the Unionist Party was the prevailing party following its success in the 1923 and 1934 general elections and 1937 provincial elections, acquiring the widespread support of Muslims, Hindus, and Sikhs in Punjab. The Unionists had created this power base by obtaining the loyalty of local landlords and influential Pirs through patronage, and the Muslim League realised that in order to win over the majority seats held by the Unionists, they too would need to exert local influence as the Unionists had done.

Ian Talbot notes that the ML’s primary strategy used to achieve this was the exploitation of religion. The Qur’an became the focal point for Muslim League activists, as pledges to vote were made using it and sermons promoting the idea of Pakistan used Quranic verses to legitimise its approval amongst supporters. Students were key proponents for the ML as they were trained by elder activists to implore voters based on communal grounds, with 1,800 members of the Punjab Muslim Student Federation and Aligarh campaigning in Punjab at its height prior to the election. David Gilmartin also contends that the ML used a ‘moral language of Muslim unity’ to acquire support, utilising ‘overtly Islamic symbols’ in their handbills and posters. Terms like millat and ummah were used to indicate universal Muslim community, while terms like qaum and qaumiyyat were used as negative equivalents to the parochial biradari.

The exploitation of religious appeal was furthered by the Muslim League’s attempt to beguile Sufi Pirs, on top of their appeasement towards Barelvis and Deobandi’s, showing that the ML did not base itself on strict theological or doctrinal matters, but vaguely appealed to all Muslims regardless of sectarian differences. One could argue that this was an attempt to foster Muslim unity, but from a political perspective, the convincing of Sufi Pirs was crucial to gain an advantage in the electorate as they had dominated the religious and political landscape in Punjab, with their influence in the region stretching back to the 11th century. Most Punjabi Muslims had offered allegiance to a Sufi Saint as their religious authority, and the Unionists had previously built their success off cultivating support from Pirs in the 1937 elections, thus giving Sufi Pirs significant political importance in the province. The ML’s enticing of Pirs was largely achieved by the creation of the Masheikh Committee, which utilised ceremonies, meetings, prayers, shrines, and the issuing of fatwas encouraging support for the Muslim League, and many Pirs switched allegiances precisely due to the factional rivalries fostered by the ML prior to the elections.

Not only did the ML exploit religious appeal but recognised the political and economic importance of gaining the support of landlords which would in turn enable the ‘client-patron economic relationship’ with tenants to gain more votes for the election. This would be achieved by exploiting the Baradari networks and appealing to primordial tribal loyalties. They held a special Gujjar Conference to attract Muslim Gujjars, on top of the swift political manoeuvre of lifting the ban on Jahanara Shahnawaz so her influence in the region could be used to appease Arain constituencies, which contained the largest Punjabi agricultural tribes. Their most notable accomplishment was the enticement of Muslim Jats and Gujjars from their intercommunal tribal loyalties to switch allegiance in support of the ML, which played a key role in the build up to the elections.

Another strategy that the ML used in Punjab was the capitalisation of the economic downturn that was endured after World War II. The ML’s promise of Pakistan, a vague reassurance of economic stability, as an alternative to the economic turmoil suffered by Punjabi villagers was also key in the switching of allegiances, as only 20% of Punjabi servicemen (800,000 which accounted for 27% of the Indian Army) found employment following the war, and the ML exploited this by opportunistically recruiting the Punjabi servicemen. Their large numbers played a key role in the elections as they constituted a large proportion of the electorate. With the culmination of these strategies, plus the fall out between Punjab Premier Malik Tiwana and Jinnah, many Muslims were forced to choose between two parties, and thus by the eve of the election the political landscape was finely poised in favour of the ML.

In Sind, economic concerns were of great importance alongside religious matters after British policies meant much of the land was transferred from Muslim hands into Hindu hands. Ayesha Jalal pinpointed the communal agitations in Sind as a key factor in the build up to the elections, as the Sind Muslim League exploited the communal divisions in order to undermine the elected government of Allah Bakhsh Soomro, who promoted a united-India. “Making an issue out of anon-issue”, Jalal writes, the pro-separatist ML activists fabricated and exaggerated the issue of the Sukkur Mazilgah mosque, where its “symbolic convergence of the identity and sovereignty over a forgotten mosque provided ammunition for those seeking office at the provincial level.” The murder of Allah Bakhsh Soomro by pro-separatist ML activists in 1943 played a huge role in gaining support for Pakistan, as political analyst Urvashi Butalia noted that had Soomro been alive, the Sind Assembly would not have supported the Pakistan resolution. But there were three other factors to note when describing the ML’s cultivation of support in Sind. Firstly, the convincing of Sufi Pirs and Saiyids in 1946 through the exploitation of religion, secondly, the Sindhi Muslim business class’ desire to drive out their Hindu competitors, brought about by the demarcation of Muslim-Hindi interests encouraged by the ML. Lastly, was the “monetarily subsidized” mobs and assassins that engaged in communal violence against Hindus and Sikhs various areas such as Jhelum, Multan, Sargodha, and the Hazara District, of which Jinnah issued no condemnation.

The Muslim League had less support in North-West Frontier Province, winning only 47% of the seats, but the activities prior to the election in this province are also revealing of the techniques the political elites used in their attempt to gain an upper hand. The Congress-led ministry in the province was headed by secular Pashtun leaders that embraced the idea of united-India as opposed to the creation of Pakistan, such as Abdul Ghaffar Khan, who preferred that a secular and independent ethnic Pashtun state be created if joining India was not viable. This standpoint created a polarisation between the Jamiyatul Ulama Sarhad (JUS) and the largely pro-Congress and pro-united India Jamiat Ulema Hind (JUH), as well as creating an impediment to Ghaffar Khan’s Khudai Khidmatgars, the nonviolent resistance movement prior to the election which promoted Hindu-Muslim unity. To counteract this, the JUS directives in the province began to intensify communal discord, just as the JUH were trying to prevent it. The JUS began to promote the idea of the Hindus posing a ‘threat’ to Muslims, with anti-Hindu fatwas and sermons delivered by mullahs, and accusations of Hindus molesting Muslim women.

Taking into consideration the various works in this field, the role of communal violence, and the exploitation of religious fervour, the sufficiency of ‘elite manipulation’ holds great weight in explaining the success of the Pakistan Movement. Whether or not it goes as far as Ayesha Jalal’s narrative that India’s partition was forced by Congress leaders who found it more convenient to offer Jinnah a ‘truncated, moth eaten’ Pakistan than to give him a political position he wanted in a united-India, elite manipulation must hold a central place in the discourse of partition due to ML’s opportunistic attempts to placate every conceivable interest group within key provinces whilst remaining ‘extraordinarily vague’ in its territorial demarcation.