Lenin vs Stalin: The Ruler that Did Most to Transform Russia, 1855-1953

Russia underwent a vast transformation in the years 1855-1953, most evidently through the displacement of the Tsarist Empire and feudal structure by the establishment of the Soviet Union and communism. Russia’s civilisation in 1855 – a feudalistic country confined by the principles of ‘autocracy, orthodoxy and nationality’ – resulted in the restriction of society, resulting in a 37% serf population and an educated class amounting to 1% . Consequently, the contrasting nature of the Soviet Union’s emergence from WWII as a global superpower can be deemed all the more remarkable, and therefore identifying of the leader most responsible for the transformation all the more significant.

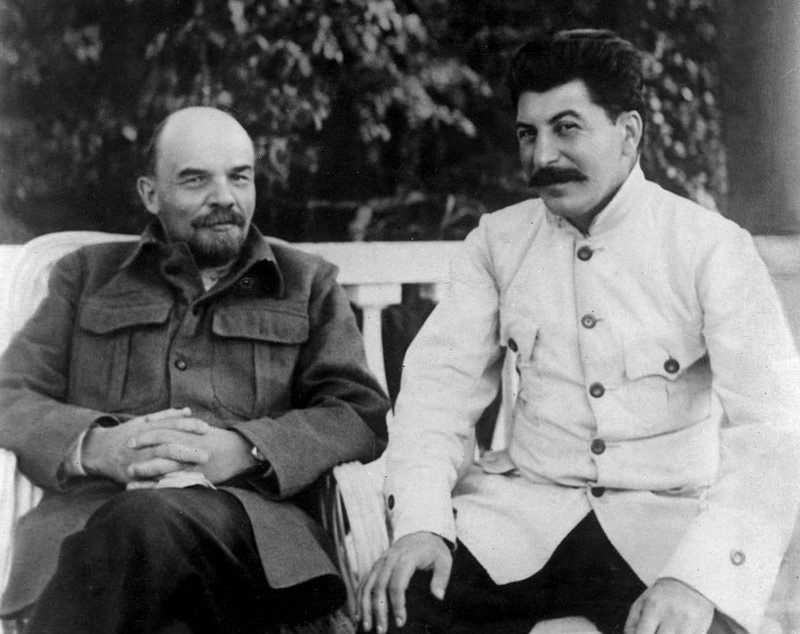

Although the essay will assess the economic, political and social change, it is important to note that certain areas of transformation hold more weight. This essay will place greater importance on economic change, due to the fact that it overlaps with social transformation and was most impactful on Russian society, however, this will not be used as a deciding factor. The political and ideological transformation will also be assessed to give a final judgement. A common misinterpretation would be to suggest that the tsarist rulers – Alexander II, Alexander III and Nicholas II – were completely redundant in Russia’s transformation due to the outdated institutions in which they governed by. However, their contributions – whether positively transformative or restricting – shaped the eventual revolution of 1917, therefore are noteworthy. However, for the most part, they viewed transformation as a restraint to their absolutist powers, subsequently, neither can be adjudicated as the most transformative ruler. This allows for the discussion to form a debate between the final two leaders; Lenin and Stalin. Lenin’s transformation can be substantiated through his coordinating of the October revolution, political modernisation and success in consolidating the revolution, arguably laying the groundworks for his successor. Despite this, Stalin’s longer-lasting rule, the fulfilment of his principal objectives, and his predecessor’s failure to finalise his changes meant that Stalin’s transformations outweighed that of Lenin’s.

When considering transformation, it is necessary to outline the aims and outcomes of reforms. Stalin’s economic aims were clear; match his communist state with the capitalist West through rapid industrialisation and collectivisation of agriculture. His aims are evident from his speech to Industrial Managers in February 1931, where he said, “We are 50 to 100 years behind the advanced countries. We must make good this difference in 10 years or go under” . The occasion of the source is noteworthy, as it took place in the third year of his first five-year plan, the most pivotal year, and clearly resembles Stalin’s desire to catch up with the capitalist-West. Although the tone may be perceived as dramatic, the directed audience were industrial managers for the fulfilment of ‘the national-economic plan’, so there would have been no need for Stalin to overstate his demands, but merely state the bare minimum required for the survival of Russia. The source can be taken at face value, as Stalin’s fear of attack from Japan, France, UK, Poland and Romania , and the grain crisis in 1928 triggered the increase in emphasis towards industrialisation. Another importance of the source is that it demonstrates that economic transformation was, arguably, of greater significance to Stalin than it was to Lenin, due to the events taking place in the late 1920s, like grain shortages, fear of war with the West and mass resentment towards the NEP. For Lenin, the economic change was required to consolidate Bolshevik power after the Civil War in 1918-20, hence the creation of the temporary NEP. For Stalin, it was a matter of life and death with the national economy at the point of breakdown, consequently, his economic transformations were considerably greater.

Remarkably, Stalin would achieve his aims through a series of five-year plans, the first of which were implemented in 1928. This period was referred to as the “Great Turn”, turning from Lenin’s New Economic Policy (NEP), which Stalin and the majority of the Communist Party felt were compromising communist ideals, not delivering sufficient economic performances, and not creating the envisaged socialist society. In the period of 1927-1939, coal, oil and iron production had all increased fourfold (coal increased 35 million tonnes to 145 million). New mines and cities like Magnitogorsk were constructed and millions of peasants moved to the cities. The collectivisation of agriculture was immensely successful, achieving 23.6% collectivisation within one year (1930), and 98% within 12 years (1941) . The figures were certainly exaggerated and there were many cases where construction was incomplete, but Stalin achieved his main goal of “dragging Russia into the 20th century” and closing the margin with the capitalist west, indicated by the first five-year plan finishing a year early in 1932. As a result, it is indisputable that Stalin’s economic transformation was of far greater than Lenin’s was. Frederic Jameson concluded he industrialisation period was a “success… transforming a peasant society into an industrial state with a literate population and remarkable scientific superstructure.”

Despite the argument that Stalin’s economic transformation was the most fulfilled being undeniable, Lenin’s economic policies were hugely significant in Russia’s transitional period of 1917-24. The condition during 1918-20, with the outbreak of war, derailed Lenin’s economic policy. He was forced to introduce the NEP in 1921 – after the relative success of “war communism” which aided the Red Army during the Civil War – with the aim of rebuilding the economy. Many Bolsheviks saw the NEP as a betrayal of socialist principles , however, it is argued that it was one of his most significant achievements as some believe that had it not been implemented, Sovnarkom would have been overthrown . Additionally, it had achieved its principal objective of rebuilding the country, and by 1928, industrial production had been restored to pre-WWI levels in 1913. Moreover, the NEP allowed for private enterprise, the reintroduction of the wage system, and return to the privately owned small industry . Lenin had also been known to say about NEP, "We are taking one step backwards, to take two steps forward later” suggesting that the NEP was not Lenin’s main objective. Although the NEP was ‘transformative’, it was restricted by failures and grew greatly unpopular, after the Grain Procurement Crisis of 1928, and the view that it compromised with capitalist elements . This prompted Stalin to replace it with collectivization in 1928, which proved to be far superior.

The New Economic Policy was a good indication of Lenin’s tactics, and revealing of his character, as it was apparent the NEP was a clear deviation from Marxist principle, yet he was willing to concede this to secure to secure material and practical support for the Bolshevik party: “[You] must attempt first to build small bridges which shall lead to a land of small peasant holdings through State Capitalism to Socialism. Otherwise, you will never lead tens of millions of people to Communism.” The audience of the source is significant, as it was not just Bolshevik party members, but supporters of the revolution, with Lenin attempting to inspire belief in the concession. The tone is pressing and coercive, as it was only his authority and determination that managed to persuade the senior Bolshevik members to pass the policy, with many uneasy with the concessions of capitalism – with the rise of Kulaks (wealthy peasants). Lenin had no concern letting the “peasants have their little bit of capitalism as long as we [Bolshevik party] keep the power” . The timing of the source is also a significant factor (1921), as, after 1918, Lenin was still suffering from a debilitating illness as a result of an unsuccessful assassination attempt, which worsened in the latter half of 1921. The message being conveyed by Lenin was that, although the NEP pointed in another direction, it would provide the economic conditions necessary for socialism to evolve. This source is highly reflective of the Lenin’s tactical flexibility and willingness to compromise in order to safeguard the revolution and ensure the survival of the regime, shown by his recognition of the NEP as a temporary solution.

All five rulers during this period can be connected through their constant pursuit of modernity, with both the tsars and Soviet leaders revolving their economic policies around industrialisation. Therefore, a key debate amongst historians is discerning the most effective in industrialising Russia. Isaac Deutscher accredits Stalin for the transformation of Russia in his biography, entitling him the most influential reformer in Russia’s history. However, Orlando Figes claims that Stalin’s industrialisation was undermined by the loss endured and was inferior to Lenin’s NEP.

“If the NEP had continued, the country would have been in a far stronger position to resist the Nazi invasion in 1941… Instead, the NEP was overturned by mass collectivization which permanently crippled Soviet agriculture and destroyed millions of peasant lives.” Figes claims Lenin’s economic policy was superior, however, this can be refuted as the NEP was viewed as a temporary expedient – which Lenin himself admitted to – and was dogged by the government’s inability to procure enough grain supplies from the peasantry, and these grain shortages prompted Stalin to introduce collectivisation. Figes’ furthers Stalin’s failures by saying “crash collectivization… had created endless misery” and the repercussion was a “national catastrophe” , and this can be conceded through the famine (1932-33) – causing the deaths of millions of peasants – and the absence of heavy agricultural machinery which handicapped many collective farms. Contrastingly, Deutscher presents a Stalin-centred argument, focusing on the success, as by the late 1930s, “… the aggregate output of her [Russia’s] mines, basic plants, and factories approached the level which the most efficient and disciplined of all continental nations, assisted by foreign capital, had reached only after three-quarters of a century of intensive industrialisation.” Additionally, he described the post-second world war Russia an “industrial giant second only to the USA” , portraying the transformation under Stalin a triumph since it had achieved the primary objective, as the state was supplied with the capital it required to transform the Soviet Union into a major industrial power.

Before evaluating their arguments, the perspectives of the historians must be identified, as they are a telling factor in the rationality of their claims. Figes’ clearly uptakes an anti-Stalinist viewpoint in his book, but this fierce stance is supported by his access to the Soviet archives, which opened in 1991, revealing the figures of brutality as a result of industrialisation. Understandably, with such figures, Figes is more condemnatory of Stalin. These specific figures were not stated by Deutscher but were mentioned in a broader perspective, which could show either impartiality or unawareness. Deutscher leaves his stance down to interpretation, stating his biography “either as a denunciation of Stalinism, or as an apology for it, and sometimes as both.” However, Deutscher has had an anti-Stalinist past, evidenced by his establishment of an anti-Stalinist group within the Polish Communist Party, and had been critical of Stalin’s policies since 1931. That being said, there is a clear contrast in tone between the historians with Deutscher being far less accusatory of Stalin, acknowledging his industrialisation as a success.

Arguably, Figes’ access to the Soviet archives gives him an advantage, as it revealed the Liberal focus on Stalin’s totalitarianism was exaggerated and falsification of information was exposed. However, a more decisive factor would be the impartiality of the two historians. Deutscher’s book, although not comprehensive, recognises the great cost of the revolution, Russia’s standard of living being inferior to that of Germany’s, as well as the loss of psychological and political freedom, stating “the giant’s robe hangs somewhat loosely upon Stalin’s figure” . Consequently, it can be said that Deutscher’s arguments are less fault-finding than that of Figes, and therefore more balanced.

Overall, Deutscher’s arguments are more convincing. Despite the revisionist account of Figes allowing him to incorporate other rulers and his access to the post-glasnost sources, Deutscher’s views are not distorted by an overly reproving and anti-Stalinist viewpoint. Instead, he maintains a critical, yet equitable perspective, recognising the human cost as a negating factor but sustains his argument. Although Deutscher’s book can be criticised for lacking an inclusive view of Russian history, the book was intended to be part of a trilogy that would include the lives of Lenin and Trotsky, which would have provided a more in-depth explanation of events, however, they were never published due to Deutscher’s death.

It would be misguided to deem the economic transformation as the deciding factor in determining the most transformative ruler, as the Soviet Union endured immense political transformation during this period. Stalin’s political aims are characterised by his policy of “Socialism in One Country”, put forward in 1924, and was the belief that Soviets must strengthen internally, differing from Leninism, Trotsky’s “permanent revolution” and the classical Marxist view that socialism must be established globally. Although it can be debated which was most practical, Stalin’s ideology was undisputedly the most transformative in the end. The outcomes of Stalin’s aims left a legacy, came to be known as ‘Stalinism’, with the development of national communism and ‘cult of personality’. Though condemned by Khrushchev in 1956, the political transformations had left their mark throughout Stalin’s final decades; in 1935-36, Stalin oversaw a new constitution; all power rested in the hands of Stalin and his Politburo, and declared “socialism, which is the first phase of communism, has basically been achieved in this country.” After the Second World War, Stalin was at described as being at the “apex of his career” by Service and regarded as the embodiment of victory and patriotism. By Stalin’s death in 1953, his armies controlled Central and Eastern Europe up to the River Elbe .

Lenin’s aims were many and varied; the foremost being his intention to start a revolution overthrow the old system and direct Russia to a socialist paradise. He played an important role in the fulfilment of the former, but the latter was not achieved. When Lenin became head of government in 1917, the focus was on consolidating Bolshevik power – and defending the inevitable Civil War – after the revolution rather than aiming to transform. Therefore, his aims in power differ greatly to Stalin, consequently prohibiting the level of transformation that Lenin actually achieved in the end. This can be evidenced, as one of his most notable political changes, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (1917), despite achieving its primary objective of establishing peace with Germany and Austria-Hungary, the Treaty was deeply unpopular and resulted in the loss of 26% of the population, 37% of arable land and 28% of industry . Although the triumph for the Reds in the Civil War was a major achievement, enabling the revolution to continue, it caused Lenin to deviate from the Marxist doctrine in order to achieve short-term goals in the march towards a socialist utopia. Opposition grew from both Left Communists and other factions in the Communist Party in the early 1920s. This was due to the belief that there had been a decline of democratic institution, with many socialists decrying Lenin’s regime, particularly due to the lack of widespread political participation, popular consultation and industrial democracy . Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin described the Bolshevik’s seizure of power as “the burial of the Russian Revolution.” Despite the considerable political progression under Lenin – the introduction of universal suffrage, secularisation and granting of workers control over enterprises – they were compromised by the temporary nature of the policies, and the non-completion of his belief that that a revolutionary vanguard and proletariat dictatorship was required as the prelude to socialism – renowned as Leninism – due to his untimely death. This non-fulfilment is one of the key factors preventing him from being deemed the most transformative ruler. Nonetheless, Lenin’s political administration laid the framework for the system of government that ruled Russia for seven decades and provided the model for later Communist-led states, which would cover a third of the world, but cannot be deemed the most transformative in terms of political change to Russia, as his framework would be completed by Stalin.

Despite Stalin being the most transformative ruler, there is the concession that he could not have done so without the foundations laid by Lenin. Service stated, “The Cheka, the forced-labour camps, the one-party state, the mono-ideological mass media… not one of these had to be invented by Stalin… Not for nothing did Stalin call himself Lenin’s disciple.” There are many parallels in their political policies seen through Lenin’s ‘war communism’ and Stalin’s ‘Great Terror’, leading to two similar famines (5 million deaths in 1921 and 6 million deaths in 1932-33) and Lenin’s ‘Red Terror’ through the implementation of the Cheka, and Stalin’s ‘Great Purge’. This rebukes the argument that Stalin’s terror weakens his transformation – one of the main fallacies used to undermine Stalin being deemed the most transformative ruler – as it is seen in both rulers. Crucially, Stalin was “not a blindly obedient Leninist” . Consequently, there is a clear transition from Leninism to Stalinism, evidenced through Socialism in One Country, a totalitarian state, a cult of personality and the subordination of communist parties to those of the Soviet Union – none of which Lenin achieved. Therefore, despite the view that Lenin laid the framework for Stalin, he was not the “successor” to Lenin and does not change the fact that Stalin was the most transformative.

Overlapping with economic transformation, there was considerable social change during this period. Upon taking power, Lenin’s regime issued a series of decrees; with the Decree on Land and Decree on Workers’ Control being the most significant immediate transformations to Russia’s socio-economic state . The implementation of war communism, although some argue that it was a transitional step towards socialism, the social impact was severe; peasants refused to co-operate in producing foods, workers began migrating from cities to the countryside where food was less scarce, and between 1918-20, Petrograd lost 72% of its population . The ‘Red Terror’, orchestrated by the Cheka, saw the execution of 512 people in a few days, with records suggesting over 140,000 were killed in total . The silver lining at the end of Lenin’s reign was the development of the “new Soviet man” . Trotsky wrote in 1924 “Man will make it his purpose to master his own feelings… to create a higher social biologic type, or, if you please, a superman” . However, the concept of the “new Soviet man” would be refined and strengthened by Stalin.

Stalin advanced the country’s sociological transition from the destitution of tsarist serfdom to the relative plenty of Communist self-determination, as peasants became urban citizens after the industrialisation and collectivization period. That being said, the human cost was staggering; 5-7 million died from the 1932-33 famine, 1.6 million were arrested in the “Great Purge”, with 700,000 shot . Despite the unnerving figures, Stalin managed to build widespread optimism and enthusiasm in large parts of the country through the five-year plans, optimised by the Stakhanovite movement which raised popularity and increased production, leading to the Soviets reaching their targets. This reflected Stalin’s utopian vision of the Soviet Union rising to unparalleled heights of human development, characterised by the “New Soviet Person”. This encouraged idiosyncrasies of both men and women, with the most important trait being selfless collectivism – on top of being full-time workers, learned and enthusiastic. The newfound sociological advancements of the people after the transition into an industrious society was not reached by Lenin, so despite Stalin’s social and economic policies being synonymous with intense labour and terror, they were evidently more impactful.

The socio-economic transformation achieved by Stalin’s five-year plans can be characterised by the Stakhanovite movement. Tatiana Fyodorova was a member of the Komsomol and later became a Stakhanovite worker after her team set a record for tunnel construction in building the Moscow metro. In 1932, she gave a speech thanking the party and Stalin: “We live so well, our hearts are so joyful, in no other country are there such happy young people as us, we're the happiest young people, and on behalf of all young people I want to thank our party and our dear comrade Stalin for this joy that we have” . The timing of the speech is significant as it is said after the success of the first five-year plan, and clearly shows the dedication towards Stalin’s objectives had heightened after the five years, demonstrated by the passionate, jubilant and spirited tone. The Stakhanovite movement encouraged workers to model themselves after Alexey Stakhanov, intending to increase worker productivity and ultimately strengthen the Communist state. The constraint of the source is the collective narrative, as she speaks “on behalf of all young people”. Many young people opposed the hard-working regime, with peasant workers absenteeism widespread, however, the resistance was easily dealt with during the 1930s. The audience is important as the speech was broadcasted across the Soviet Union, therefore shows the implementation of socialist emulation , and the personalities – in this case, Tatiana and Stakhanov – that were used as models to uplift Russian society, reflecting Stalin’s message of portraying socialism as the leading ideology with capitalism crumbling amid the Wall Street crash .

Autocracy remained throughout 1855-1917; therefore, the transformation by the tsars during this period cannot be compared to Lenin and Stalin. However, there were noteworthy changes that impacted the social, political and economic landscape of Russia and cannot be disregarded. The Emancipation of Serfs Edict (1861) under Alexander II’s reign was seemingly transformative, but it was flawed in several aspects. The 49-year redemption payment and loss of holdings meant the peasantry did not benefit. Nevertheless, M.S. Anderson argued ‘the grant of individual freedom and a minimum of civil rights to twenty million people… was the single greatest liberating measure in the whole history of Europe” . Despite the social development in Russian society, the tsar was not interested in humanitarian refinements and the main intention of improving the economy had failed.

On the international relations front, Russia’s participation at the Congress of Berlin in 1878 demonstrated the recovery of Russia’s international position. However, Alexander II’s attempts political reforms were defective as his economic changes. The introduction of local governments in the form of zemstvos was supervised by the bureaucracy, and adjustments to the judicial system only affected a small section of the population. However, reforms in education and brief relaxation of censorship allowed for social advancement and the start of political consciousness, with the emergence of a new intelligentsia in the form of Populists, who would later become the Social Revolutionaries; they would become a crucial insurgent group in the overthrowing of Tsarist Empire. Overall, the potential in Alexander II’s reforms did not match the outcome, as they did not go far enough and no consequential change was made. Transformation under Alexander II’s reign was restricted by his concern to appease the nobility, which alienated the support of the liberals, radicals and peasants, leading to his assassination in 1881.

Alexander III’s reign halted any hope of progression started by his father, and his autocratic aims prevented any form of transformation. Although his repressive stance “did allow a period of stability during which government control could be strengthened and Russian confidence and prestige restored” , Alexander III’s chauvinism – through the policy of Russification – clearly outlined a retreat into the past. He would also end the reforms made by his father, abolishing justice of the peace, reducing the power of the zemstvos and increasing censorship. Alexander III’s achievements were minimal, but his authoritarian style of rule led to an unintended increase in middle-class resentment – indicating social development – beset on constitutional change. Besides this, the appointment of Finance Ministers Vshnegradsky (1887-1892) and Sergei Witte (1892-1903) were his only other achievements. Despite the minor economic and social change, autocracy remained and would be continued by his successor; therefore, it would be accurate to describe Alexander III as the least transformative of the rulers.

Orlando Figes depicted Nicholas II’s reign as “the worst of both worlds: a tsar determined to rule from the throne yet quite incapable of exercising power” . His aims are best characterised by his response to provincial zemstvo of Tver appealing for an extension of representative institutions, “I will uphold the principle of autocracy as firmly and as unflinchingly as my late unforgettable father.” Although Nicholas was persistent with autocracy, this did not prevent political and economic change while he was tsar. However, it would be inaccurate to credit these changes to Nicholas, as they were primarily down to Witte. Witte’s reforms saw the creation of the gold standard for the rouble, Trans-Siberian railway and increase in foreign investment . Abraham Ascher stated, “Russia’s economic progress in the eleven years of Witte’s tenure as minister of finance was by every standard, remarkable.”

Politically, Nicholas was just as stubborn describing constitutional reform as “senseless dreams” . Political reforms were only achieved after the 1905 revolution, once again under the supervision of Witte, with the establishment of the October Manifesto. This should have been a momentous transformation with the introduction of the duma , but with the exclusion of the word ‘constitution’ and use of the fundamental laws of April 1906, Nicholas bypassed this, which highlighted the superficial nature of the reforms. Although his reign witnessed significant political and economic change, this was in spite of Nicholas II whose lack of competence as a ruler was one of the reasons for the collapse of the Tsarist Empire, and therefore cannot be considered the most transformative ruler.

Overall, Stalin was the most transformative ruler for Russia in the period 1855-1953. Lenin’s transformations were crucial in developing Russia, as he masterminded the Bolshevik take-over, kept the social state intact through the Civil War, and had absolute control for the party, which only had to socially engineer Russia into a socialist utopia. Lenin, of course, never came to see this utopia and this prevents him from being adjudged as the most transformative ruler. His reforms can only be deemed the foundations for the Soviet Union’s transition to a communist state, as Stalin would transform Leninism into Stalinism, with its most representative feature being Socialism in One Country. All five rulers focused their economic policies on industrialisation, therefore making it a predominant factor in determining the most transformative ruler – hence the essay’s focus on this matter – and while all rulers made noteworthy reforms, it was only Stalin that managed to fully transform Russia into a global superpower.